It’s been a long time since my last post, since I could find a fraction of time to think, unraveling my own emotions and thoughts enough to get them down in written form. For months they have instead traveled only through my mind, that space somewhere between my ears and my heart, wisps of imagination in the midst of excitement, transitions, fears, sadness, and delight. As a full-time doctoral student and a full time educator, I often have the sense that my time is not fully mine. I rush from assignment to class, to a presentation then a collaborative session. Grateful am I for a grounding in meditation and Buddhist philosophy; my gerbil mind has learned to find rest in between breaths and in the sangha of Running Buddies. I give thanks as well for being raised in an independent church focused more on love, kindness, and community building than on scripture, tradition, and One True God; in this place my heart grew resilient, supple, less likely to break into a million pieces, as Parker J. Palmer writes, than to split open, if sometimes deeply and painfully, finding solace in compassion, holding great joy and great suffering together in the same chasm.

Recently I posted a photograph on social media of a fat, pointy, milkweed pod, bursting open, white and brown and gray and black, revealing nothing at all of its starry summer-time fashion. Oranges, purples, and almost reds were traded for the monochromatic vision of fall turning to winter in the Midwest, and it was stunning in the rare afternoon sunshine. “It’s easy to find beauty in the bursting heart of summer,” I wrote, “but for me the barrenness of fall reveals the truest promise of life.” This promissory note is signed in seeds of every shape and size. These cells, while waiting for their moment to shine, will be blown by the wind, carried by the birds, and even hitched snugly to the bottom edge of my sweater, to be plucked out and dropped somewhere down the trail. As the milkweed stood stout and naked, I stooped, low and overdressed, to admire and capture the possibility exposed by the splitting of a barbed, silver seam on a fall afternoon.

Five years ago, on a fall evening, my parents returned home from a family party to find my little brother dead, cigarette butt crushed beneath his fallen body, his heart stopped, breath gone, his death caused by an accidental overdose. My little brother, and I repeat the word little again with purpose, struggled most of his life with chemical addiction of various kinds – inhalants, cigarettes, weed and benzos, but it was opioids that held him fast, and that in the end killed him, and several other little brothers we knew that fall and winter.

My little brother was never really little. Born close to ten pounds heavy, everything about him was big – his head, his smile, his eyes behind his cokebottle glasses. Quickly, my little brother became my big little brother, towering over me by almost a foot by the time we both could drive. Although there were certainly times he let me know how much bigger he was than me, sometimes with threats to my dumbass boyfriends, other times with brotherly frustration toward my own dumbass attitude, he was largely – pun intended – a gentle giant to me. When I was very young I used to put my head next to his sticky baby hands, knowing his fingers would find their way into my silky hair, which he would twist and pat and stroke, a safety blanket of an action for both of us, until his hand was tangled and my hair knotted, and our mom had to separate two screeching children from their own mess. As we grew up, he would sometimes laugh when we compared our hands, his dwarfing mine early on, and he practically howled with delight when our oldest niece, just learning to really talk, argued with me that, “No. He’s your big brother. You’re so little. He’s so big. You are little sister, like my little sister.” Not true, but I understood her reasoning and found it in many ways reassuring. I’d always wanted a big brother, anyway.

Only a few weeks before my brother died, he called me to do some real reassuring, trying to help me calm my anxiety in the first months as a new teacher. Like many young educators, imposter syndrome had caught me tightly, and a deep striving for perfectionism had left me nearly paralyzed. I was rarely eating, barely sleeping, and ignoring calls from my parents and sisters. Yet when a call came through from my brother, who for years has been lost in his own drug addled world, I picked up quickly. We talked briefly about his work, about Mom and Dad coming out to visit me in a few weeks, and before hanging up he gave me one piece of advice, “Keep your head up, sis,” he said sagely. “You’ll be okay – you just gotta keep your head up.”

___

Last night, as we got ready for bed, someone opened the back door and Sydney, my brother’s dog, bolted out into the blackness. My brother got Sydney as a puppy. A beautiful Australian Blue Heeler crossed with a Black Lab, she has one blue eye, one brown eye and a coat speckled with silver spots. She is crazy and always has been despite training, special diets, and her own doggie herbal anxiety remedies. She loved my brother, and he loved her. When he would come home from work, he would open the door, open his arms, and she would jump up into them, the happiest she was all day.

Once my brother was arrested then released, left by the police who had picked him up, not safely at our home or a hospital, but at a local, shitty motel to suffer detox alone. He called me, and I packed him a bag of clean clothes, underwear, and socks. I picked up saltines, electrolyte drinks, and even a few abhorrent Coca Colas, having no idea what to bring a drug addict in the throes of coming down. When I arrived, I knocked on his door, praying he would answer, and he did, soaked in sweat, ashen, crying. He was still high – I could tell – but no longer past lucidity, and my big little brother collapsed in my arms, heaving with shame and telling me he understood if I wanted to leave while I tried to wrap my arms around his huge frame. I rocked him as best I could while he cried and hiccoughed. When hours later I went to leave knowing he would be okay for the moment, Adam looked at me, pleading, “Take care of my puppy. Take care of my baby Syd.” Back at home, alone in my parents’ house, I put Sydney on her leash and shoved a handful of biscuits into my pocket, and we walked across the street to the Calumet Trail. I made Syd sit, stay, and before I took her off leash, I also sat down on the trail, wrapped my arms around her, and stayed myself.

When Sydney ran off last night, I know I wasn’t the only one thinking, She is looking for her boy. Many of us are looking for her boy. Last night we looked instead for Sydney, headlamps, flashlights, and cellular phones glowing up and down the unlit street. She didn’t go far, and I could hear her collars jangling quietly one against the other the whole while we called for her. In the dark, she’d snuck from our back door, to the tree on the hill where my brother used to stand and smoke, circling around to finally come to my call, tail tucked, head bowed, but mission complete, I like to think, having visited her boy, then come home. I hugged her, kissed her silky head, as I softly scolded, “Sydney! No running away!” Then I stroked her thick ears, and gave her a treat – hardly good training but undoubtedly what my little brother would have done.

Every year on November 27 our hearts split open, any healing from the year past catches up, and again the chasm feels wide and gaping, at least for me, for my parents, for my family. Into this chasm, we plunge in our own ways. We make plans to see a movie all together, the way we always did with Adam, tubs of popcorn, jugs of cola, and Twizzlers galore, judgement suspended on who broke whose heart for a bit as well as on caloric intake. We buy thick steaks and crab legs, his favorite, and I always contemplate buying a pack of Marlboros, then pass and instead have a beer, though my little brother rarely drank. We rake leaves all day, and turn them into smoke and ash. We look at pictures, and send text messages, and we laugh and cry and breathe. And we give thanks, for Adam, for our family, for the lives that have grown bigger over the last five years, the time that he has been gone, an eternity and a moment in one. Perhaps most importantly we let ourselves split open but not apart, chasms capable of holding others’ suffering with loving kindness, “using the insight that comes in the dark*” to find and offer a bit of light to others. Sometimes, in late fall along the Calumet we stand, naked hearts exposed, bursting at our silver seams with the possibility of dreams that dance on the wind, of life that comes from death, of the colors that in summer will be revealed only when the barrenness of fall is nothing but a photograph.

______

Over the last 15 years, nearly half a million Americans have died from lethal drug overdoses. For several years in a row now, lethal drug overdoses have claimed the lives of almost 50,000 people in America each year. Sixty percent of these overdoses are related to opioids and synthetic variants, many likely accidental. There are many ways we can work together to address addiction in our lives, but in my opinion all of these methods stem first and foremost from recognizing the humanity of the addict and the way each of us – addict or not – strives to fill the chasms in our lives. Working together to practice compassion, kindness, deep listening, and caring for ourselves and our neighbors, we can create more resilient, supple hearts that, instead of breaking into bits in the darkness, gently open to seed the ground with love, forgiveness, and the colors of summer year round.

May you be happy and healthy.

May you be safe and free.

May you take care of yourself with ease.

Love,

Emily Bee

Loving Kindness Practice by Jack Kornfield

American Society of Addiction Medicine Facts and Figures on Opioid Addiction

The Atlantic The Fight for the Overdose Drug

Mother Jones Opioid Users Are Finally Getting This Lifesaving Overdose Drug

*quote from Healing the Heart of Democracy by Parker J. Palmer

Milkweed along the trail.

Looks suspicious….

Dad, me, and my big little brother on Mother’s Day. Mom took the picture, of course :).

Crazy Eye.

Syd enjoying the trail.

With Adam’s baby – Sydney Pup.

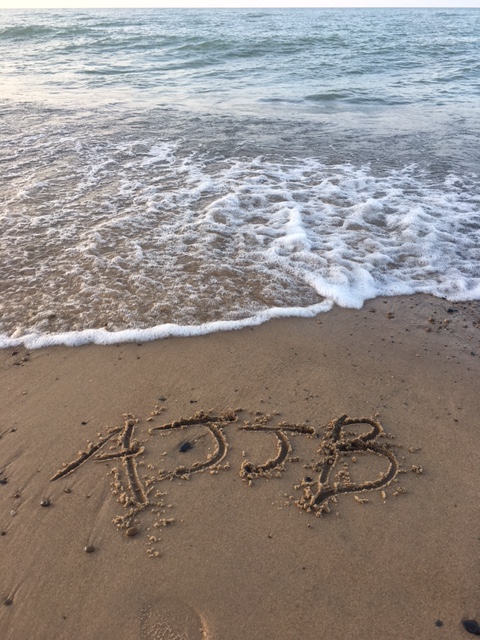

AJJB

❤️ ❤️❤️‼️

Emily, once again your words touch me deeply. You have a gift….you ARE a gift!

Much love, Sandy

Thank you so much for sharing your beautiful words and heart with us. So courageous and healing. Sending you and your family all my love. ❤️

Your words touched my soul Emily. My siblings and I still talk every year about the day the earth stood still – the day we lost our 14 year old brother. That was 1971. But I assure you that the overwhelming pain will ease.

Good morning Emily,

Milkweed Promise. Beautiful. You most certainly have a gift for writing.

Memories can make our heart sing or make our heart cry. Thank you for sharing the memories that touch your heart so deeply. —

I enjoyed visiting with you Thanksgiving day. I look forward to our next visit.

I located Krista Tippett’s O Being. I know I’ll be visiting her often. Krista is featured in my recent Lion’s Roar, formally Shambhala Sun magazine.

Wishing You a lovely day & an enjoyable run.

Namaste’,

Love & Peace, Eula Faye

On Sun, Nov 27, 2016 at 4:48 PM, (Inside Parentheses) wrote:

> Emily Bee posted: “It’s been a long time since my last post, since I could > find a fraction of time to think, unraveling my own emotions and thoughts > enough to get them down in written form. For months they have instead > traveled only through my mind, that space somewhere bet” >

Ms. Eula Faye! I so enjoyed our Thanksgiving dinner. I think I am still full from all the food! Lion’s Roar is one of my favorite publications. I am looking forward to seeing you when I am home again in December!

Emily, I do not know you but I am friends with your sister Anne. I have watched as both of my parents suffered some sort of addiction throughout my entire childhood through my 40’s. It’s unfortunate that I lost my mom five years ago and my father 17 years ago. My mother suffered terribly with back pain from arachnoiditis. I watched as she withered away within five years of using pain meds. It was heartbreaking. I’m left with a very large hole in my heart and soul, she was only 63 and the best friend I could ever ask for. She lives in my heart now. My father beat his addiction to alcohol but suffered a rare form of cancer and lived for 6 months from diagnosis. His death was a bit more bearable because I had my mom to gently guide me and support me. The milkweed is grown in my yard every year and my children and I have raised butterflies from the moment the egg is visible. We set them free in remeberence of both of my parents. A simple weed that provides such comfort and awe in this world. The Monarch, the meaning of life. Short lived, but provides such beauty even though the life span is so short. Your brother died very young, I hope that you continue writing about addiction and your love for him. I’ve read all of your stories and each one has its own meaning, but all represent your soul. How beautiful! You have such talent. Thank you for sharing. ❤️